Saved by Music

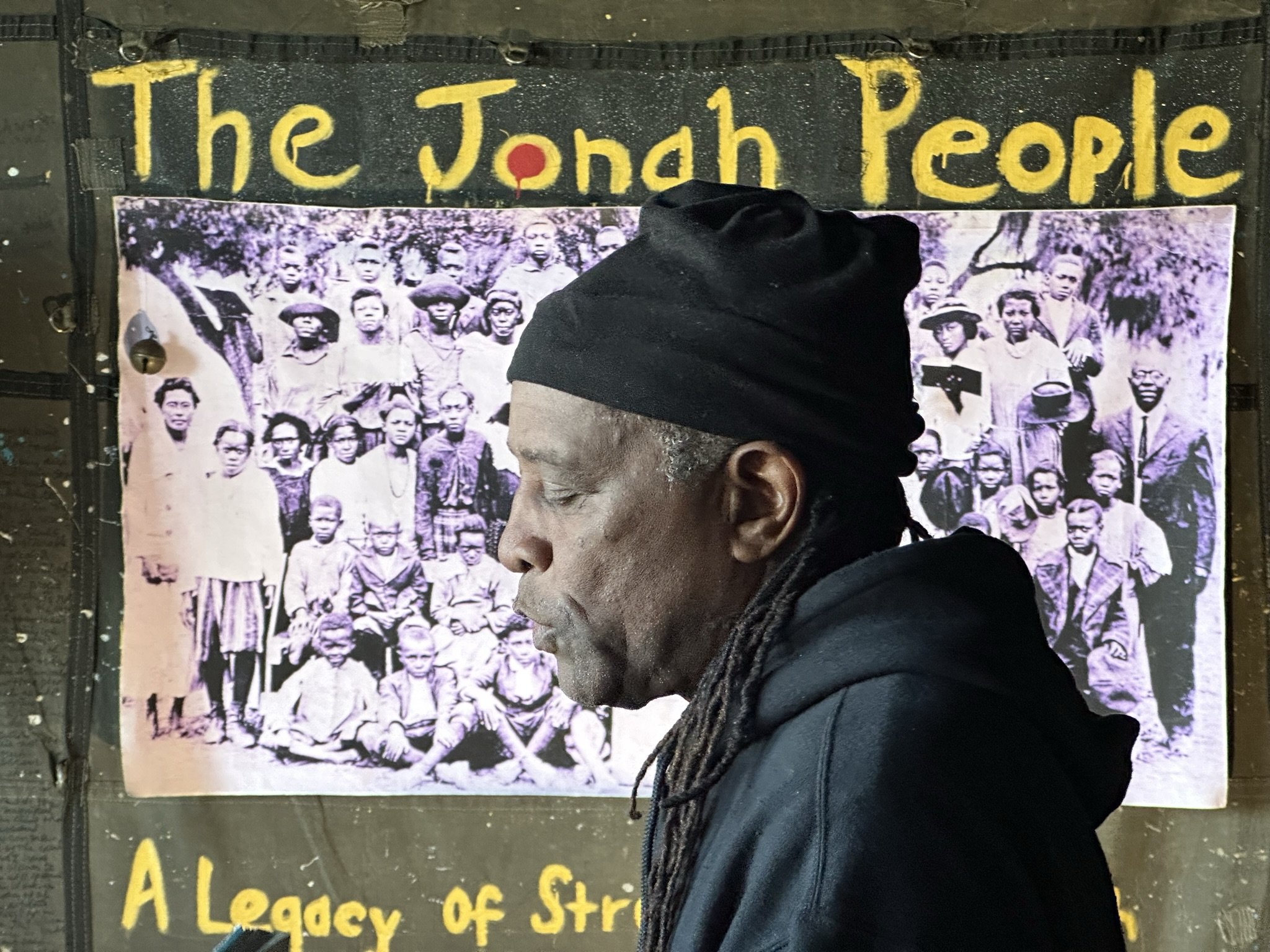

“Imagery and sound, to me, are one and the same,” Lokumbe says. He speaks of grasping the totality of a composition before mapping out its details. At the same time, The Jonah People was five years in the making from start to finish: on June 10, 2022, Lokumbe placed a yellow paint print of his right palm on a tapestry he keeps to record his creative process.

The Jonah People might also be described as a summation of his entire life’s work. His most ambitious and intricately collaborative project to date, it brings together Lokumbe’s legacies as a trailblazing, category-defying composer and performer; as a poet and playwright; and as a mentor and educator who has dedicated his art to the liberation of human thought. (While many jazz trumpeters follow the custom of inscribing their own name on the bell of the horn, Lokumbe has engraved his instrument with the word “liberation.”)

Lokumbe was only 13 when he realized his life’s vocation was to be a musician. “I’ve always seen the immediate impact music has on human behavior,” he says. “It had the ability to save my life. It saved my ancestors in the cotton field as well and gave them the strength to withstand the unrelenting sun. They withstood that by singing when it got too hot to even talk.”

Born Marvin Peterson in 1948, he grew up on a Texas cotton farm that his great-grandfather Silas Burgess had acquired. He later was given the name Lokumbe (“the spirit that lives in the wind”) after living in Kenya among the Maasai in the late 1970s (he’d traveled there to find healing for a nearly fatal illness); “Hannibal” honors the ancient Carthaginian general who fought against ancient Rome.

The Jonah People draws on Lokumbe’s own family history, which he says was communicated to him by one of his shaman ancestors and by an aunt to whom the record of their struggles over generations had been passed down. Silas and his mother Asase had survived the hellish voyage of the Middle Passage across the Atlantic that is portrayed in the opera and were then sold at auction. Following his enslavement, Silas made his way to Texas and raised 22 children from two wives.

As a teenager, Lokumbe fell in love with jazz when he discovered John Coltrane on recordings. He started his own group and quickly earned a reputation for his trumpet artistry. He moved to New York City in 1970 and performed and recorded with numerous jazz legends, including the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, the drummers Elvin Jones and Roy Haynes, and the pianist, composer, and bandleader Gil Evans. Lokumbe also made albums in the U.S. and Europe with his own band. Characteristically, he became known for working across multiple jazz idioms, from hard bop to free jazz.

Not an “I” story, but a “We” story

Alongside his jazz career, Lokumbe began experimenting with large-scale compositions combining jazz and classical forces (orchestra, chorus and soloists). Lokumbe’s breakthrough work in this vein was African Portraits (premiered in 1990 at Carnegie Hall and widely performed since). It addresses much of the same material as The Jonah People, tracing the legacy of people enslaved in the United States over centuries as well as their indispensable contributions to American culture.

Lokumbe likes to refer to these large-scale choral-symphonic creations as “spiritatorios” (his take on the classical idea of the oratorio). Among his other works are compositions honoring Medgar Evers (God, Mississippi and a Man Called Evers), Rosa Parks (Dear Mrs. Parks), and even his great-grandfather Silas (Can You Hear God Crying?). Another major composition explores the idea of creation itself (One Land, One River, One People, written for the Philadelphia Orchestra in 2015).

What sets The Jonah People apart from the rest of Lokumbe’s work—in addition to its sheer scope and many tiers of collaboration—is that it synthesizes the musical, visual, poetic and theatrical dimensions that for this artist are all integral parts of his original vision, realizing all of this on the stage to a degree he has never attempted before. Which is another way of saying that The Jonah People is a full-on opera.

Opera is all about collaboration, and The Jonah People would not make its impact without the contributions of the top-tier artists who comprise the creative team—the set design, projection, costumes, lighting and animation—and of course the performers, from the huge cast of singers, actors and dancers to the orchestra, chorus, solo instrumentalists, jazz band and drum ensemble.

But Lokumbe also sees The Jonah People as a collaboration with the audience that he hopes will bring healing. Referring back to his trip to the forest, he points out that he first has to “completely annihilate my ego” before he’s ready to receive what the Creator has deemed “worthy for the people to experience.” Though Lokumbe has drawn on episodes from his own family history, the work is intended to represent the ordeal and the hope of all of the Jonah People: not an “I” story but a “we” story.